the alexander walking technique

We generally don’t think about our walking style. As toddlers, we learned and imitated those around us. We took on their postures and gait styles. Our environment, activities and footwear also influenced our gait. Everything is generally fine until we head out on the trail. Repetitive strain injuries creep up and we are hobbled by shin splints (pain at the front of the shin), plantar fasciitis (tendonitis of the foot) or chondromalacia patella (pain and uneven wearing of the kneecap). Many of these conditions can be prevented by fine tuning your walking technique.

In some walking patterns, the heel leads the gait. The forward swinging leg extends far in front; the heel strike is vigorous, leading to the heel absorbing much of the impact of the body. Emphasis on the heel strike causes the small shin muscle (Tibialis Anterior) to overwork in lifting and extending the foot. This may lead to shin splints. The higher impact of this gait can also lead to painful knee joints.

Other walking patterns involve emphasis on the toe stance and overuse of calf muscles (Gastrocnemius and Soleus), walking with the heels held higher than the fore foot. This is common during up-hill walking and in some running styles. This will cause the calf muscles to shorten. The strength and length imbalance created between the calves and the shin muscles can cause shin splints and lead to plantar fasciitis.

Muscle imbalances in the Quadriceps muscles (especially Vastus Medialis and Vastus Lateralis) can cause poor kneecap (patella) tracking and lead to deep knee pain when walking up or down hilly terrain. This will lead to chondromalacia patella.

Weak butt muscles (gluteus maximus) leads to backward leaning walking style. This is generally inefficient and can cause the back to fatigue.

These injuries will prevent you from achieving your walking goals. We suggest that you become mindful of your own walking style and alter it to minimise possible chronic overuse injuries. The following is a natural walking style based on the Alexander Technique. Try using it while performing your walking workouts. Try it first on city walks where the terrain in smooth. It will help you focus on technique more than the terrain. Later, try it on wilderness trails as well. It will become second nature soon enough.

The Alexander Technique is an educational process that uses verbal and tactile feedback to teach improved use of the individual’s body by identifying and changing inefficient habits that cause stress, fatigue, and pain. If you find it difficult to do this on your own, try it with a friend/observer, or take a few coaching lessons from a qualified practitioner.

In some walking patterns, the heel leads the gait. The forward swinging leg extends far in front; the heel strike is vigorous, leading to the heel absorbing much of the impact of the body. Emphasis on the heel strike causes the small shin muscle (Tibialis Anterior) to overwork in lifting and extending the foot. This may lead to shin splints. The higher impact of this gait can also lead to painful knee joints.

Other walking patterns involve emphasis on the toe stance and overuse of calf muscles (Gastrocnemius and Soleus), walking with the heels held higher than the fore foot. This is common during up-hill walking and in some running styles. This will cause the calf muscles to shorten. The strength and length imbalance created between the calves and the shin muscles can cause shin splints and lead to plantar fasciitis.

Muscle imbalances in the Quadriceps muscles (especially Vastus Medialis and Vastus Lateralis) can cause poor kneecap (patella) tracking and lead to deep knee pain when walking up or down hilly terrain. This will lead to chondromalacia patella.

Weak butt muscles (gluteus maximus) leads to backward leaning walking style. This is generally inefficient and can cause the back to fatigue.

These injuries will prevent you from achieving your walking goals. We suggest that you become mindful of your own walking style and alter it to minimise possible chronic overuse injuries. The following is a natural walking style based on the Alexander Technique. Try using it while performing your walking workouts. Try it first on city walks where the terrain in smooth. It will help you focus on technique more than the terrain. Later, try it on wilderness trails as well. It will become second nature soon enough.

The Alexander Technique is an educational process that uses verbal and tactile feedback to teach improved use of the individual’s body by identifying and changing inefficient habits that cause stress, fatigue, and pain. If you find it difficult to do this on your own, try it with a friend/observer, or take a few coaching lessons from a qualified practitioner.

The Head Leads - The Stance Phase

The fundamental tenet of the Alexander Technique is that the head leads a lengthening spine which leads the body into movement. Just this frequently reduces the effort of standing. There should be an even weight distribution from the front to the back of both feet.

There is a slight forward lean initiated at the ankles. Hinging at the hips can lead to back strain. Try standing straight, elongate your spine and ‘fall forward’ by leaning. At some point you will step forward to prevent a fall. That lean aids in the efficiency of the walking style. The faster your pace the greater the angle of your posture.

There is a slight forward lean initiated at the ankles. Hinging at the hips can lead to back strain. Try standing straight, elongate your spine and ‘fall forward’ by leaning. At some point you will step forward to prevent a fall. That lean aids in the efficiency of the walking style. The faster your pace the greater the angle of your posture.

From the Calves - The Toe Off

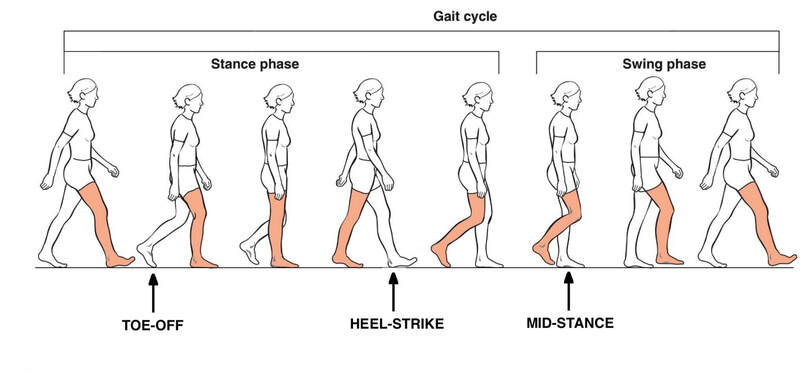

Most of us think walking comes mainly from the front of the thighs (Quadriceps) - which lift the legs as we walk - but the initial movement in walking starts behind the leg. The calf lifts the heel off the ground, which places the foot on the ball of the toes. The leg bends at the knee and hip joint.

At this moment, experiencing your weight on the ball of one foot and the other foot fully planted, in Mid-Stance, you don’t have to shift sideways onto the supporting leg for balance. You allow the leg on the ball of the foot to push off and swing forward. The calves take the heels off the ground, allowing the foot room to swing through.

At this moment, experiencing your weight on the ball of one foot and the other foot fully planted, in Mid-Stance, you don’t have to shift sideways onto the supporting leg for balance. You allow the leg on the ball of the foot to push off and swing forward. The calves take the heels off the ground, allowing the foot room to swing through.

From the Knees - The Swing Phase

Once the leg swings forward, gently bend the knee just enough to swing the leg without catching the toes on the ground. The foot should remain relaxed and neutral. Try shortening your stride and gently placing your foot down directly below your nose.

With this decreased impact, fatigue is minimised. As the terrain changes, your stride will adapt, shorter strides for uphill walking (keep your heal level, or lower than your toes) and moderate strides for flat or downhill terrain. Keep your toes under your nose as a general guideline for stride length.

Keep at it and soon you will find this natural walking style becoming easier. If you start experiencing some pain from walking review your gait and adjust it to maximise efficiency and minimise impact.

With this decreased impact, fatigue is minimised. As the terrain changes, your stride will adapt, shorter strides for uphill walking (keep your heal level, or lower than your toes) and moderate strides for flat or downhill terrain. Keep your toes under your nose as a general guideline for stride length.

Keep at it and soon you will find this natural walking style becoming easier. If you start experiencing some pain from walking review your gait and adjust it to maximise efficiency and minimise impact.

Mountaineering Walking Techniques

The following are mountaineering techniques that can come in handy on steeper terrain. Whether walking up or down-hill, these techniques can reduce ankle and knee strain. By changing your foot placement or turning your body at an angle from the hill, you can keep your feet flat with a more normal forward flex of the ankles and knees. The techniques are described in the uphill direction. They can also be performed in downhill direction.

As the slope steepens slightly, it will begin to get awkward to keep your toes pointing directly uphill. Try splaying them slightly outward, Duck Step.

As the slope gets steeper still, heading straight upward in Duck Step can itself cause ankle strain. Then it's time to turn sideways to the slope and ascend diagonally for a more relaxed, comfortable step. Keep your feet flat and parallel. Adjust the angle depending on the steepness of the terrain. This is called the French Step.

Move diagonally upward in a two-step sequence. Start from a position of balance, your inside (uphill) foot in front of and above the trailing outside (downhill) foot.

From this position, bring the outside (downhill) foot in front of and above the inside foot. The outside leg crosses over and in front of the inside leg. Because this crossover can compromise the stability, and make the next step difficult, remember to step forward and up. Bring the inside foot up from behind and place it again in front of the outside foot. Keep the weight of your body over your feet. Avoid leaning into the slope, this will minimise friction and your foots ability to purchase the terrain and creates the danger of slipping. Step on lower-angled spots and natural irregularities on the terrain to ease ankle strain and conserve energy.

To change direction (switchback) on a diagonal ascent of a slope, move your outside (downhill) foot forward, onto the same level as your uphill foot. Turn into the slope, moving your inside (uphill) foot to point in the new direction and slightly uphill. You are now facing into the slope, standing with feet splayed outward. Return to the in-balance position by turning your attention to the foot that is still pointing in the old direction. Move this foot above and in front of the other foot. You're now back in balance and facing the new direction of travel.

As the slope steepens slightly, it will begin to get awkward to keep your toes pointing directly uphill. Try splaying them slightly outward, Duck Step.

As the slope gets steeper still, heading straight upward in Duck Step can itself cause ankle strain. Then it's time to turn sideways to the slope and ascend diagonally for a more relaxed, comfortable step. Keep your feet flat and parallel. Adjust the angle depending on the steepness of the terrain. This is called the French Step.

Move diagonally upward in a two-step sequence. Start from a position of balance, your inside (uphill) foot in front of and above the trailing outside (downhill) foot.

From this position, bring the outside (downhill) foot in front of and above the inside foot. The outside leg crosses over and in front of the inside leg. Because this crossover can compromise the stability, and make the next step difficult, remember to step forward and up. Bring the inside foot up from behind and place it again in front of the outside foot. Keep the weight of your body over your feet. Avoid leaning into the slope, this will minimise friction and your foots ability to purchase the terrain and creates the danger of slipping. Step on lower-angled spots and natural irregularities on the terrain to ease ankle strain and conserve energy.

To change direction (switchback) on a diagonal ascent of a slope, move your outside (downhill) foot forward, onto the same level as your uphill foot. Turn into the slope, moving your inside (uphill) foot to point in the new direction and slightly uphill. You are now facing into the slope, standing with feet splayed outward. Return to the in-balance position by turning your attention to the foot that is still pointing in the old direction. Move this foot above and in front of the other foot. You're now back in balance and facing the new direction of travel.

The Rest Step technique takes pressure and strain off your muscles and transfers it to your bone structure. Although it's mainly useful on snow, or on climbs at elevation where endurance is important, it can be employed on any trail with steep slopes.

As you step forward on an incline, lock your downhill (rear) knee and keep all your weight on that rear leg. Swing your other leg forward, relax the muscles in that leg. Once your forward foot comes to rest on the ground, keep it relaxed so that there's no weight on it. You can stop in that position for as long as you need to.

When you're ready to take the next step, shift your weight to the front foot, step forward with the other and lock the rear knee again, repeating the entire process.

The locked rear knee provides support for your weight without requiring help from the leg muscles. That means your leg, hip and back muscles get a rest, if only for a short moment. Stay paused in that position for however long it takes to avoid running out of breath.

Continuous movement is a great strain on your muscles. Moreover, stopping and starting, like slowing down and speeding up, wastes energy. The key to preserving your energy for the long haul is to be economical in all your movements.

As you step forward on an incline, lock your downhill (rear) knee and keep all your weight on that rear leg. Swing your other leg forward, relax the muscles in that leg. Once your forward foot comes to rest on the ground, keep it relaxed so that there's no weight on it. You can stop in that position for as long as you need to.

When you're ready to take the next step, shift your weight to the front foot, step forward with the other and lock the rear knee again, repeating the entire process.

The locked rear knee provides support for your weight without requiring help from the leg muscles. That means your leg, hip and back muscles get a rest, if only for a short moment. Stay paused in that position for however long it takes to avoid running out of breath.

Continuous movement is a great strain on your muscles. Moreover, stopping and starting, like slowing down and speeding up, wastes energy. The key to preserving your energy for the long haul is to be economical in all your movements.